Sunday, June 19, 2011

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Najib for dialogue to resolve religious issues

Najib for dialogue to resolve religious issues

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

He said, however, the dialogues must hinge on sincerity that manifested from maturity to achieve understanding and create harmony among races and religions in the country.

"In the context of relationship among religions, if such dialogues are supported and mediated by respected religious leaders, it will produce multiple positive impacts for the people," he said when opening the 54th National Quran Reciters Assembly here.

Also present was Sarawak Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud.

Twenty-nine qari (male Quran reciters) and qariah (female Quran reciter) are due to take part in the assembly themed "1Malaysia 1Ummah" at the Dewan Majlis Islam Sarawak. "Suffice to say, the price of peace is very high," said Najib, adding that the government was continuously monitoring religious sensitivities so as to prevent irresponsible quarters from sowing religious discord.

On the theme "1Malaysia 1Ummah", he said it brought a deep wisdom and fulfilled the needs of the people and Muslims.

He said the social contract, historical background and the federal constitution should be capitalised as the framework to guide the people in building a progressive and harmonious 1Malaysia, which culminated in a great 1Ummah.

"Under this scenario, promoting racial tolerance and acceptance among various races, namely the Malays, Chinese, Indians, Melanau, Iban, Kadazan-Dusun, Bidayuh, Bajau, Senoi and more than other 200 ethnic communities should continuously be empowered," said the prime minister. The government would not neglect the Islamic development agenda in its strive to turn Malaysia into a high-income country by 2020, he added.

He said the government acknowledged the role played by the religious community in the march towards Vision 2020, which was proven by raising the allowances of Kafa teachers, takmir teachers and imams to elevate them from the poverty line starting this year.

On the assembly, he said it was a symbol of the government's ongoing commitment to uphold the Al-Quran. "It is such an important annual event, it will definitely bring continuous impact to the 1Ummah strength".Bernama

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Public disagree with OWC’s approach on marriage

KOTA KINABALU: A local lawyer and activist has taken Kuala Lumpur-based Obedient Wives Club (OWC) to task for likening marital sex as ‘first class prostitution’ as it is very degrading to both women and men.

“It is unfortunate that the approach by OWC is to direct the focus of marriage on sex.

“This creates a very negative self-image for both women and men because it assumes that the only way to keep the marriage is to sexualise it and ignore the other important components of a marital partnership such as common goals and hobbies, communication and personal development, respect and love and joint responsibility in child rearing,” said Nilakrisna James.

She was commenting on the recent statement by OWC, providing sex lessons to help wives ‘serve their husbands better than a first-class prostitute’ to help promote harmonious marriages and counter social ills.

Nila reckons that developing a positive self-image and sexual confidence is important for women but this has nothing to do with keeping a man loyal.

She said women should automatically do this for themselves for their own mental and physical well-being and realise that being obedient has nothing to do with being submissive and lascivious in marital sex to the point where they cannot say no.

Nila who is also very active in child and women’s rights movement, stressed women should have the right to say no to sex and not feel pressured by the idea that their husbands would leave them if they do not perform like a whore.

She pointed out women should have sex on their own terms.

“Every couple in a relationship defines their own personal sexual needs and where one man might find a wanton hussy interesting, another might find it totally filthy and unattractive.

“Therefore, women should not delude themselves into thinking that there is a set formula to what turns a man on in bed,” she said.

However, Nila told The Borneo Post that she would give the OWC credit for sensationalizing and opening up the Malaysian people to a debate about sex and if we can openly discuss these matters without shame and embarrassment, then there is hope yet for an open civil society in this country.

“Women, above all else, should be responsible for developing a nation that could learn to respect women the way they are without always sexualising them and demeaning their status,” Nila added.

Thursday, June 2, 2011

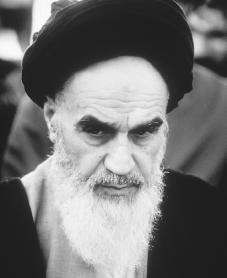

Ayatollah Khomeini (24 Sept 1902- 3 June 1989)

Born: September 24, 1902

Khomein, Persia

Died: June 3, 1989

Tehran, Iran

Iranian head of state and religious leader

Ayatollah Khomeini was the founder and supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The only leader in the Muslim world who combined political and religious authority as a head of state, he took office in 1979.

Early life and education

Ayatollah Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini was born on September 24, 1902, according to most sources. The title Ayatollah (the Sign of God) reflected his scholarly religious standing in the Shia Islamic tradition. His first name, Ruhollah (the Spirit of God), is a common name in spite of its religious meaning, and his last name is taken from his birthplace, the town of Khomein, which is about 200 miles south of Tehran, Iran's capital city. His father, Mustapha Musavi, was the chief cleric (those with religious authority) of the town and was murdered only five months after the birth of Ruhollah. The child was raised by his mother (Hajar) and aunt (Sahebeh), both of whom died when Ruhollah was about fifteen years old.

Ayatollah Khomeini's life after childhood went through three different phases. The first phase, from 1908 to 1962, was marked mainly by training, teaching, and writing in the field of Islamic studies. At the age of six he began to study the Koran, Islam's holy book, and also elementary Persian, an ancient language of Iran. Later, he completed his studies in Islamic law, ethics, and spiritual philosophy under the supervision of Ayatollah Abdul Karim Haeri-ye Yazdi, in Qom, where he also got married and had two sons and three daughters. Although during this scholarly phase of his life Khomeini was not politically active, the nature of his studies, teachings, and writings revealed that he firmly believed in political activism by clerics (religious leaders).

Preparation for political leadership

The second phase of Khomeini's life, from 1962 to 1979, was marked by political activism which was greatly influenced by his strict, religious interpretation of Shia Islam. He practically launched his fight against the shah's regime (the king's rule) in 1962, which led to the eruption of a religious and political rebellion on June 5, 1963. This date (fifteenth of Khurdad in the Iranian solar calendar) is regarded by the revolutionists as the turning point in the history of the Islamic movement in Iran. The shah's bloody crushing of the uprising was followed by the exile (forced removal) of Khomeini in 1964, first to Iraq then to France.

Khomeini's religious and political ideas became more extreme and his entry into active political opposition reflected a combination of events in his life. First, the deaths of the two leading Iranian religious leaders left leadership open to Khomeini. Second, although ever since the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944) to power in the 1920s, the clerical class had been on the defensive because of his movements away from certain

Reproduced by permission of

Founding the Islamic Republic of Iran

The third phase of Khomeini's life began with his return to Iran from exile on February 1, 1979, after Muhammad Reza Shah had been forced to step down two weeks earlier. On February 11 revolutionary forces loyal to Khomeini seized power in Iran, and Khomeini emerged as the founder and the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

From the perspective of Khomeini and his followers, the Iranian Revolution went through several "revolutionary" phases. The first phase began with Khomeini's appointment of Mehdi Bazargan as the head of the "provisional government" on February 5, 1979, and ended with his fall on November 6, two days after the capture of the U.S. embassy (the U.S. headquarters in Iran).

The second revolution was marked by the elimination of mainly nationalist forces, or forces devoted to the interests of a culture. As early as August 20, 1979, twenty-two newspapers that clashed with Khomeini's views were ordered closed. In terms of foreign policy, the landmarks of the second revolution were the destruction of U.S.-Iran relations and the admission of the shah to the United States on October 22, 1979. Two weeks later, Khomeini instructed Iranian students to "expand with all their might their attacks against the United States" in order to force the extradition (legal surrender) of the shah. The seizure of the American embassy on November 4 led to 444 days of agonizing dispute between the United States and Iran until the release of the hostages on January 21, 1981.

The so-called third revolution began with Khomeini's dismissal of President Abul Hassan Bani-Sadr on June 22, 1981. Bani-Sadr's fate was a result of Khomeini's determination to eliminate from power any individual or group that could stand in the way of the ideal Islamic Republic of Iran. This government, however, had yet to be molded thoroughly according to his interpretation of Islam. In terms of foreign policy, the main characteristics of the third revolution were the continuation of the Iraq-Iran war, expanded efforts to export the "Islamic revolution," and increasing relations with the Soviet Union, a once-powerful nation that was made up of Russia and several other smaller nations.

The revolution began going through yet a fourth phase in late 1982. Domestically, the clerical class had combined its control, prevented land distribution, and promoted the role of the private citizens. Internationally, Iran sought a means of ending its status as an outcast and tried to distance itself from terrorist groups. It expanded commercial relations with Western Europe, China, Japan, and Turkey and reduced interaction with the Soviet Union. Iran also claimed that the door was open for re-establishing relations with the United States.

After the revolution

In November of 1986 President Ronald Reagan (1911–) admitted that the United States had secretly supplied some arms to Iran for their war against Iraq. This controversy led to a lengthy governmental investigation to see if federal laws had been violated in what would become known as the Iran-Contra affair.

In 1988 Khomeini and Iran accepted a cease-fire with Iraq after being pressured by the United Nations, a multi-national, peace-keeping organization. On February 14, 1989, Khomeini sentenced writer Salman Rushdie (1947–) to death, without a trial, in a legal ruling called a fatwa. Khomeini deemed Rushdie's novel "The Satanic Verses" to be blasphemous, or insulting to God, because of its unflattering portrait of Islam.

Before his death from cancer in Iran on June 3, 1989, Khomeini designated President Ali Khamenei to succeed him. Khomeini is still a popular figure to Iranians. Each year on the anniversary of his death, hundreds of thousands of people attend a ceremony at his shrine at the Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery.

For More Information

Bakhash, Shaul. The Region of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Hiro, Dilip. Iran Under the Ayatollahs. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1985.

Moin, Baqer. Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2000.

Rajaee, Farhang. Islamic Values and World View: Khomeyni on Man, the State and International Politics. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1983.

Read more: Ayatollah Khomeini Biography - life, childhood, name, death, history, mother, book, old, information, born, year http://www.notablebiographies.com/Jo-Ki/Khomeini-Ayatollah.html#ixzz1OB4VMIL5